Environment and Human Adaptation

Environment

Geographical Location

The Iglulik Inuit are Inuit members or Northern American who were once a nomadic culture, but due to many factors they have seemed to settle permanently near the country of Canada within the territory of Nunavut. Within this territory is the land of Igloolik which the Iglulik Inuits derive their name from, meaning “there is a house there”. Another name the Iglulik Inuit go by is also, Iglulingmuit. Their home stretches from the Igluligaarjuk land to the north of the Melville Peninsula and just across the Baffin Island.

Climate

As for their climate, the Iglulingmuit live in the Arctic regions of Nunavut, and so the temperatures do tend to be colder than other regions, but depending on the community it will vary. For Igloolik in particular, year round they have an average cool temperature of 0.0°C to -18.23°C, however despite their low temperatures they experience lower chances of precipitation as of late. With 7.55 millimetres (0.3 inches) of precipitation and less than 20 days of rain a year and a snow depth of 5.5mm (0.22in) max and an average of 0.48mm (0.02in). They go most of the year without rainfall, 346.55 days (94.95%), yet with a humidity of 85% of the year. This kind of climate forces the Iglulinmuit to work with their surroundings and not have to change any of their adaptations much throughout the year despite their Arctic Tundra climate.

Population Setting

The home of the Iglulik Inuit is much more rural, however with continuous economic development, the idea of “rural” and “suburban” wouldn’t quite for the community. They live in a community of hundreds with schools, western stores, and even commercial enterprises within the land. Since the late 40’s and early 50’s their connection to the West had brought in both rural and suburban community life while maintaining their cultural traditions. They had churches, homes, stores, but nothing too urban such as skyscrapers, factories and the such. All that said, the Iglulik are most certainly “isolated” in a way that they do not fight with other communities for food and shelter resources, but due to environmental issues resources are still a struggle for the Iglulik despite not needing a resource guard.

|

| Dryas Integrifolia |

Flora and Fauna

The environment of Igloolik comprises a diverse biodiversity of both animals and plants that live within this region. Some animals that the Iglulik may run into within their communities consist mainly of many sea animals and sea mammals that wander the land. Some such as Belugas, Killer Whales, and various Polar bears. Among them are also smaller sea birds and mammals like Arctic Foxes, several sea birds, Snow Geese, falcons and lemmings. Aside from the large sea mammals, there are a few Musk Ox and Caribou that will wander about, though lately with fewer sightings due to over hunting and climate change. Some of the vegetation of Igloolik varied around the land, however Dryas integrifolia, a flower within the rose familia, is quite popular and common within the area. Some other examples of vegetation are different variations of moss such as Plagiomnium medium, or Alpine Thyme Moss is spread throughout the land along with Bryum moss that have large impacts on controlling the land’s nitrogen levels. Most of the vegetation that lives within Igloolik are arctic specific plants that have adapted to live in the Arctic Tundra climate, compared to other vegetation you might see in southern warmer climates.

Environmental Stresses

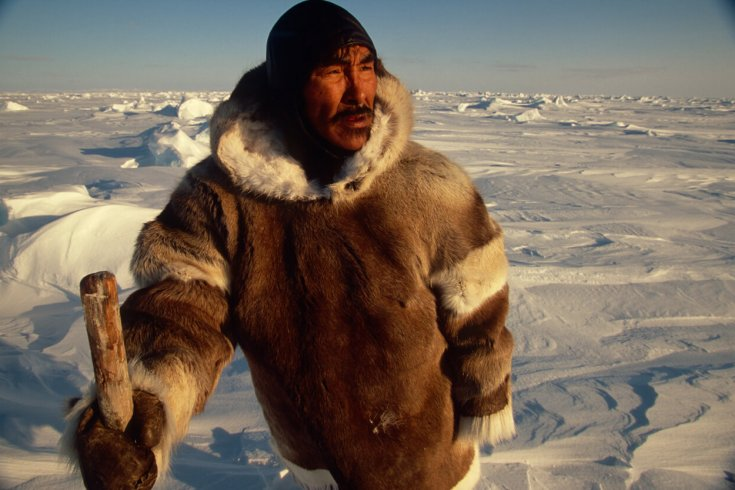

In the past, the Iglulik Inuit had to have adapted to many different stresses off their environments in order to survive through the means of hunting and gathering, as well as using the furs of the animals that live there to stay warm in their Arctic climate. However, with an increase of social impact and climate change, their adaptations have changed as well. While most young men would go out to learn how to hunt full time year round for their family, newer generations of Inuit have learned to prefer the taste of Western store bought food compared to the food that is caught in the wild. This social change comes from the Westernization of the 1950’s as well as the need of the families needed to resort to store bought food over hunting and thus younger generations adapting and becoming acquitted to this new type of food. Though Westernization was partially due to this, climate change had a bigger role in the decline of hunting and local fauna became much too scarce to reliably hunt. Since the change of nomadic hunting lifestyle had been swapped over to a permanent settlement situation in the 1960’s, they became reliant on technology such as snowmobiles and motorized boats in order to continue to survive in the environment they live in. These technologies being dependent on their survival, it requires all hunting trips to be booked in advance by days, weeks or even months, though because of climate change the uncertainty of the weather may ruin a whole month of hunting. They have adapted to their permanent settlement situation with the use of technology, however, the Iglulik continue to run into problems they must overcome and adapt to. So, with the uncertainty of food technology, comes the reliance of store bought foods and eventually the decline of hunting and gathering overall.

Adaptations

Physical

Mainly due to the rigid arctic world they live in, the Igulik Inuit throughout their history relied on a diet of extremely fatty animals such as seals, caribou, and other sea mammals they hunted. This diet had effectively changed their physiology in different ways.

Digestion

In order to adapt to their diet of high fatty mammals, their physiology had changed in order to digest these fatty acids much easier than those who do not retain such Inuit genomes. The mutations that the inuit have lowers their LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and the chemicals that would normally increase their insulin levels. This is allegedly in order to decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes since their diets consist of fatty omega-3 acids that would normally cause diseases such as those.

Height

Another physical adaptation that their bodies had seen throughout their generations is decreased height. Because of the mutation to decrease risk of cardiovascular disease and such their fatty acid profiles have differed drastically compared to others. Due to the fact that height is often regulated by their fatty acid profiles, this decreased the heights of the Iglulik Inuit making them shorter than the average person.

Cultural

Nomadic -> Permanent

A cultural adaptation of the Iglulik Inuit is their way of living. Of course, that is very general, however, it is worth noting that they were once nomadic peoples who would travel with their resources in order to survive. As the herd moved, so did they and would live in temporary homes. This would all end near the 1950’s and the 1960’s in which white people would come and introduce technology to the Iglulik Inuit and change their lifestyles so drastically that they benefited from living in a permanent residence rather than that of a nomadic lifestyle. They were able to rely on the technology to build homes, churches, small towns, and increase their social economic lifestyles and thus increase their life into a more luxurious one of comfort.

Hunting and Gathering and Travelling

With the Westernization of their nomadic lives, so did their practice of being hunters and gatherers. With their introduction of technology, the Iglulik Inuit now permanently live in one area, however this will increase the difficulty of hunting. Forcing the Inuit to rely on snowmobiles and motorized vehicles in order to drive off to where their produce will lay and making them dependent on technology for hunting otherwise it would not be sensible to travel by foot to hunt as they would need to travel for days simply to get resources to survive.

Generational Tastes and Jobs

As each generation of Ingulik Inuit becomes accustomed to Western practices and food this will result in newer generations preferring “newer” things than that of the “old”. Despite technology helping the Inuit hunt and gather, these machines and expeditions must be prepared in advance and make fresh produce more scarce for families to obtain, so to adapt to this families would go out and buy store bought produce rather than hunted produce more often than not. These foods would soon then be preferred by younger generations and reduce the need for overall hunting. Most younger men of the Iglulik Inuits would hunt full time for their family, however with this change of taste and insecure reliance on technology most young adults would change this. They would go from full time hunting to part time, as they may have a part time job back at home, or not hunt at all and go to their full time jobs in order to be able to afford their new expensive tastes.

Language and Gender Roles

Language

The language of the Iglulik Inuit is that of Inuktitut. This language resides in the Inuit–Aleut language family in which it derives from. Though Inuktitut is a language that has multiple dialects, depending on the location, the Iglulik do not use any of the dialects outside of the main language. What separates Inuktitut from other languages is that it is considered to be a polysynthetic language, meaning this language consists of words and phrases that are much longer than that of say English for example.

When it comes to their written language, it was not discovered until they had come into contact with Europeans which introduced written language to them. The writing system of their language is syllabic and uses sets of symbols that pronounce different syllables in order to form words. With the introduction of their written system, it was much more young before eventually being standardized using Roman syllables and with this standardization came for reliable translations of the written language to their spoken pronunciations.

Gender Roles

Before the introduction of Western styled technology and practices, gender roles between men and women were pretty basic and common with a few exceptions. The men were mainly hunters would go out all day in order to hunt and gather food, furs, and the such for their family, and the women were caretakers who would tend to the men’s wounds, fix meals, take care of the children, and sew garments for their families to wear. Though they weren’t limited to only knowing these skills, they were welcome, if they had the time, to learn the skills of men. However, with the introduction of technology and European and Western practices, some of these roles have changed a bit. As the social economy of the Inuit developed, they would welcome women to do more than they have before. With the introduction of jobs with wages, Women would not only become primary caretakers of their family, but as well as the “breadwinner” of sorts as they would go gain full time or part jobs to support their family, wake up taking care of their children, and come home to husbands to look after. Though they wouldn’t be the only ones with jobs, most men would still either be partially or fully hunting leaving the Women to take care of everything else. Once again, these gender roles are not as strict as they would be in other cultures, but this is the most practised. Despite the restrictions not being very strict at all, these roles have physical consequences for those who perform them. Men are put into dangerous situations daily with dangerous animals and harsh weather conditions, while the women are constantly pushing their bodies to the bring with constantly overworking themselves physically and mentally at work and home in order to keep their households together. The main reason for this Man and Woman gender role being the most accepted, is due to the physical biology of men and women making men “naturally” stronger to hunt which leaves women at home.

The youth of the Inuit understand this as simple and enter their respective roles, but with the introduction of Europeans both and young and women go to school and church, but as they get older, the older men of the youth will soon learn they need to replace their grandfathers and other men who hunt and leave school early in order to hunt, however with Westernization they learned to take some toll off of their poor mothers as well and take a part time job to provide for their families in more ways than just hunting. Young women on the other hand will continue to either go to school, or help their mothers back at home by working full time and taking care of the men who return from hunting expeditions.

“The Blessed Curse”

The main character of this story would be welcomed into the Iglulik Inuit culture depending on the time and era of which they come. For a pre-European exposure context, they would be considered a sipiniq, someone who isn’t necessarily defined as either role. These people would be accepted socially as the gender they were designated to be. So the protagonist would most likely be in a woman gender role, however because of the relaxed practices off gender role, they may learn how to hunt at some point and even join the men in hunts as long as it didn’t interfere with home care. For a time of post European introduction, or something modern, the protagonist would most likely be accepted socially as the gender they appear to be, but because of their physical strength, they would probably be taking over a man’s role in their society in order to help out their family’s burden and hunt.

Subsistence and Economy

Subsistence.

The traditional subsistence pattern of Iglulik Inuit culture is based on a combination of fishing, hunting, and gathering of wild plants and animals. During the warmer months, the Iglulik Inuit would hunt for caribou and seal, and fish for Arctic char and cod. In the colder months, they would hunt for sea mammals such as walrus, whale, and seal, in addition to fishing for Arctic cod. They would also hunt for polar bears and birds, and gather wild plants and berries.

In recent years, Iglulik Inuit culture has begun to shift away from this traditional subsistence pattern. The Iglulik Inuit now have access to a wider variety of food sources, including store-bought groceries, which has enabled them to diversify their diets. Additionally, the introduction of technology such as snowmobiles and rifles has allowed them to more easily and effectively hunt game in a more efficient way, but even with this new technology they tend to prefer store bought goods. This shift in subsistence patterns has also been influenced by changes in the natural environment, such as the decrease in sea ice due to climate change.

The division of labor tends to be based upon age and sex, but not necessarily social class. Women are traditionally the primary providers of food, and responsible for traditional means of gaining food such as fishing and gathering as men are responsible for hunting large animals such as caribou, polar bear, and seal. Young children are responsible for tending to the dogs and helping with various tasks such as carrying supplies and water. For more modern ways of obtaining food, the men hunt and work part time jobs, while the women and children will help around the house while their mother’s are working part time jobs to be able to afford food at the grocery store.

Their diet is limited by their environment and the availability of food sources varies depending on their location and whether or not the technology they have, snow mobiles and such, can make it to where their food lies. Much of their diet is based upon traditional foods such as seal, caribou, fish, and various plants and berries, but they also rely heavily on sea mammals, which are harder and more labour intensive to obtain. Though not reliant on it, Narwhal is a good example of a sea mammal that the Inglulik hunt that is rare and difficult to secure as food.

When it came to food, due to the scarcity of their food, they would not produce any surplus of their food due to the fact that the Inuit would rely on different forms of hunting, fishing, and gathering for their food resources. This would meet their needs to survive, but not enough to create a surplus.

The main value of their food and wealth was maintained through a system of “sharing”. This system was based on the idea of reciprocity, which states that members of a community should share resources so that everyone has access to the basic necessities of life. It is referred to as “qalimaaq” in Inuktitut; Through qalimaaq, families and others are expected to share their resources with one another, such as their catches, general food and supplies, and sometimes even their money and items of value.

Despite their system of sharing, they were also traditionally engaged in various trade. In the past, trade was conducted with other Inuit communities as well as with Europeans when they arrived in Nunavut. This trade was mostly in the form of bartering, as the Iglulik Inuit did not use currency at the time. However, in more recent modern times the Iglulik Inuit will stray away from traditional trade practices and use the Canadian Dollar for most economic purposes when purchasing goods and services.

Before the introduction of modernization in the 1950’s and grocery stores, the system of sharing and trade benefited the Iglulik Inuit with increased access to goods and resources, including items that are not available locally, such as metal tools, clothing, and weapons. Trade during this time has also allowed the Iglulik Inuit to participate in the larger economy and to access goods and resources that they would not have been able to outside of basic necessities that usually only Europeans would have access to. Interestingly enough, the Iglulik could only benefit from trade within their culture as it spreads their culture and gives them valuable resources, however some may argue that increased trade eventually came to a point where trade would be abolished as eventually the Canadian Dollar would become the universal currency within their territories and eventually abolish the need of trade.

Marriage, Descent, and Kinship Patterns

The Inglulik Inuit have come to practice a form of arranged marriage where the Parents arrange marriages between their children when they children are of marrying age. Marrying age depends on their gender which would be about 15-16 for females and 19 or 20 for most males. The Inglulik Inuit do not practice any form of cousin marriage as there is a strong taboo against marriage between closely related individuals and because of such those who are related are not considered eligible for marriage. And as there are incest taboos, the Iglulik Inuit were not strictly monogamous, despite it being the most common form of marriage. Polygyny was an option for men who would like to marry, however the reasoning for the lack of polygyny is due to the fact that they cannot afford multiple wives making most marriages strictly monogamous.

For marriage to be considered, they should not be related closely in any way, but the families will create a kinship between the families once they have found a partner through betrothal and the birth of a child. Most in the community will consider the couple to be married after the birth of their first child. While marriages may be arranged, they tend to usually only be set up for what would benefit both families the most in a social setting rather than economically. There isn’t necessarily any contractual obligation between the married couple aside from the arranged marriage.

After marriage, the Iglulik Inuit would favor a patrilocal residence pattern near their patrilineal kinship descent, but it wasn’t strict. It would have flexibility where the new family would live near or by the father’s side of the family.

Most, if not all, marriages are heterosexual nuclear families as homosexuality has always been frowned upon amongst the Inglulik Inuit forcing LGBT+ Inuit to stay closeted and enter heterosexual monogamous relationships to avoid being out casted by society.

Kinship

Traditionally, Iglulik Inuit descent is traced through the patrilineal line. This means descent is traced through the father's line, and a person's name usually comes from their father's name. For example, a person whose father's name is Akaak would usually have a name that begins with Aka- such as Akaatak or Akaapik. This descent pattern is different from other Inuit groups who trace descent through the matrilineal line.

Their naming pattern follows this as well as in their kinship system, names are based on the relationships between individuals. Children are given names based on their parents, grandparents, or other family members. Similar to the previous example, a child may be given the name of their maternal grandmother, or a parent may give their child the name of their own father. Siblings may also have similar or related names, and aunts and uncles may be given names that reflect their relationship to their nieces and nephews. Additionally, the names of deceased relatives may be recycled and given to another family member.

Social & Political Organization

The society of the Iglulik Inuit is generally egalitarian since it is based on a shared sense of responsibility and mutual respect and does not have a rigid class system. All members of the community have the same rights and obligations and work together to ensure their collective wellbeing.

They also have a decentralized political system, which is managed by regional councils and local leaders. Their political power is determined by the community with elders and other respected members of the community having the most influence. The leaders tend to be chosen based on their experience, skills, and knowledge of Inuit culture and values. The elders are also asked for advice, and so that decisions can be made in a collective manner. They also rely on a system of self-governance, called the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, which is based on their traditional values and beliefs.

The Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit promotes the idea of responsibility and respect, and emphasizes the importance of collaboration and consensus among the Inuit people. This system of governance helps to ensure that the Inuit maintain their traditional values and beliefs, while also taking into account the more modern needs of their community.

In terms of punishments for breaking laws, the Iglulik Inuit use a variety of methods. These can include verbal reprimands, fines, public shaming, or even banishment from the community. In some cases, the “criminal” may be asked to provide compensation or restitution, such as returning stolen items or paying a fine. In more serious cases, the “criminal” may be sent to a camp, where they can learn to take responsibility for their actions and make amends with the community before returning and being accepted once again within their society.

Violence

Violence is generally viewed negatively in the Iglulik Inuit culture, and is only used as a last resort. Physical violence is not accepted, and is considered a violation of traditional values. However, the community may also recognize that violence can sometimes be necessary in order to protect the community from danger, and that it can be used in self-defense. The Iglulik believe that violence should only be used when all other options have been used up, and that it should be used with some form of restraint. Since it is seen as a violation of traditional values the negative effects tend to breach trust within the community.

Belief Systems & the Arts

Religion

The Iglulik Inuit people traditionally practice a polytheistic animistic religion which is closely related to other northern Indigenous religions like Inuit Shamanism and Spirituality. These spiritual practices are related to other indigenous religions found around the world, most notably with the practices of certain Native American tribes. As a result, the Iglulik Inuit do not have a single creation story. Instead, their spiritual beliefs are based on the respect for the land, animals, and spirits that inhabit their environment. This belief system is based on millennia of oral history passed down through generations of Inuit elders.

Iglulik Inuit spiritual beliefs and practices are centered around the concept of Inua, the universal life force. Inua is thought to be responsible for the creation and maintenance of the universe, and the Iglulik Inuit believe that humans are connected to this life force through their relationship to the land and their ancestors. However, Inua is not the only god they believe in as the Iglulik Inuit have numerous gods and goddesses that they seek guidance from. These deities are known as sisiutit or “the great ones”. Some of these gods and goddesses include: Amaguq, a wolf god; Malina, sun goddess; Igaluk, moon goddess; or Tekkeitsertok, the god of caribou.

In order to honor and communicate with these deities and spiritual beings, the Iglulik Inuit practice various rituals and ceremonies. These include drumming, dancing, singing, and storytelling, as well as the offering of food and other gifts. These traditional practices are still practiced today by the Iglulik Inuit, and they continue to be an important part of their culture and religion.

Religion is a major part of their culture and is deeply rooted in their everyday lives. They follow traditional spiritual practices that center on the belief that all living things are connected, and that the spirit world influences the physical world. Observing these practices and culture is part of the making of offerings and taboos, as well as traditional seasonal festivals as well as their everyday lives.

Art

Artwork

The Iglulik Inuit culture has a long history of expressing their beliefs and values through art. Artwork plays an important role in their society and is used to communicate stories, prayers, and teachings. Traditional artwork is used to decorate masks and clothing, decorate homes and boats, and depict spiritual beings. It is also used to depict scenes from everyday life, such as hunting and fishing, as well as to express spiritual beliefs. Artwork is used to honor the spirits and to ask for help and protection.

Music

Music is an important part of the Iglulik Inuit culture, as they use it to express their emotions, honor their ancestors, and thank the spirits. It is used to tell stories, to express feelings, and to provide entertainment. Traditional music is performed using drums, rattles, and flutes and is often accompanied by singing and dancing. It is an important way for the Iglulik Inuit to communicate their values and beliefs and to share their culture with the world.

The artwork of the Iglulik Inuit also serves as a form of entertainment. Artwork is used to communicate stories through storytelling, dance, and song. This helps to preserve the culture and the language of the Iglulik Inuit. It also helps to strengthen the bonds between people, as it provides a way for them to connect with their past and share their stories with others.

The artwork of the Iglulik Inuit is also used to express emotion and to show respect to the spirit world. It is a way to honor their ancestors and to thank the spirits for their blessings. Artwork provides a visual representation of the values of the Iglulik Inuit and helps to keep their culture alive.

Performance

Dances are performed for a variety of purposes, such as birthday celebrations, weddings, funerals, and other ceremonies. Many dances are accompanied by drumming and singing, and some dances are accompanied by masks or costumes. Traditional dances include the Drum Dance, the Walrus Dance, the Bear Dance, and the Kiviok Dance. These dances are often accompanied by songs or stories, and can be seen as a form of storytelling. In addition to these traditional dances, modern Inuit dances have also been created, such as the Qaggiq Dance, which is performed at the Iglulik Summer Games.

Religious Art

Like materialistic artwork mentioned before, Religious art to the Iglulik Inuit is envisioned through various forms of art such as carvings, masks, and sculptures. These pieces of art usually depict spiritual figures, such as shamans, and stories from Inuit mythology. Carvings of animals and birds are also popular and are used to represent the story of these creatures. Additionally, the Iglulik Inuit are well known for their stone and ivory carvings of spirits and mythical creatures, which often feature intricate details and complex designs while masks are also used to depict spirits and other spiritual beings. These masks often feature elements of nature and the animals of the region. To accompany religious ceremonies and rituals, the Iglulik also carve their own handmade drums.

Conclusion

The Inuit culture of Iglulik has been affected by other cultures — both positively and negatively.

One of the most positive impacts of outside cultures has been the introduction of new technologies and new ways of doing things. This has allowed the Inuit to be more efficient in their everyday tasks, such as hunting and fishing, as well as allowing them to take advantage of modern conveniences such as electricity and running water.

On the other hand, outside cultures have also had a negative impact on the Inuit culture of Iglulik. One example is the introduction of industrialized fishing, which has led to a significant decrease in the number of fish in local waters. This has had a major impact on the Inuit way of life as they rely heavily on fishing for food and basic necessities. In addition, the introduction of western culture has caused a shift in traditional Inuit culture, with some of the younger generations now seeing western values as the norm. This has caused a rift between generations, as the elders struggle to maintain their traditional culture while the youth adapt to more modern values.

Overall, the Iglulik Inuit still have a strong influence in the modern world. They have adapted to the changing world by embracing new technologies and ways of doing things, while still maintaining their traditional culture. They are also playing an increasingly important role in the Arctic, as their knowledge and expertise of the region is invaluable to modern research and development.

Bibliography

“Adaptation to High-Fat Diet, Cold Had Profound Effect on Inuit, Including Shorter Height.” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 17 Sept. 2015, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/09/150917160034.htm#:~:text=Researchers%20have%20found%20unique%20genetic,differ%20in%20their%20physiological%20response.

ASSOCIATION, QIKIQTANI INUIT. Qikiqtani Truth Commission: Community Histories 1950-1975. INHABIT MEDIA INC, 2014.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Inuit-people. Accessed 26 November 2022.

Auset, Brandi. The Goddess Guide: Exploring the Attributes and Correspondences of the Divine Feminine. Llewellyn Publications, 2009.

Compton, Richard. “Inuktitut.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 13 Dec. 2016, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuktitut.

Conlon, Paula. Iglulik Inuit Drum Dance: Past, Present, and Future. University of Oklahoma,https://www.se.edu/native-american/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2019/09/NAS-2009-Proceedings-Conlon.pdf.

Council, Inuit Circumpolar and Williamson, Karla Jessen. "Inuit". Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 Nov. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Inuit-people. Accessed 26 November 2022.

Craufurd-lewis, Michael. “Iglulingmuit.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 Feb. 2006, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/iglulik-inuit.

Damas, David. “Central Eskimo Systems of Food Sharing.” Ethnology, vol. 11, no. 3, 1972, pp. 220–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3773217. Accessed 7 Dec. 2022.

Damas, David. “Three Kinship Systems from the Central Arctic.” Arctic Anthropology, vol. 12, no. 1, 1975, pp. 10–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40315859. Accessed 7 Dec. 2022.

DERRY, ALISON M, et al. “Soil Nutrients and Vegetation Characteristics of a Dorset/Thule Sitein the Canadian Arctic.” View of Soil Nutrients and Vegetation Characteristics of a Dorset/Thule Site in the Canadian Arctic, 17 Oct. 1997, https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/arctic/article/view/63979/47914.

Exchange, Knightsbridge Foreign, and Admin. “All about Nunavut - Currency Exchange Canada.” KnightsbridgeFX, 19 Dec. 2019, https://www.knightsbridgefx.com/all-about-nunavut/.

Ford, James D., et al. “Vulnerability to Climate Change in Igloolik, Nunavut: What We Can Learn from the Past and Present.” Polar Record, vol. 42, no. 2, Oct. 2006, pp. 127–138., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0032247406005122.

Freeman, Minnie Aodla. “Inuit.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 8 June 2010, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuit.

“Igloolik Research Center.” INTERACT, 24 Feb. 2021, https://eu-interact.org/field-sites/igloolik-research-center/.

“Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada Climate.” Igloolik, Nunavut, CA Climate Zone, Monthly Averages, Historical Weather Data, https://tcktcktck.org/canada/nunavut/igloolik.

“Igloolik: Food (in)Security in an Arctic Inuit Community.” WeADAPT, 24 Apr. 2019, https://www.weadapt.org/placemarks/maps/view/23761.

“Inuit Art History.” Inuit Sculptures Art Gallery, https://www.inuitsculptures.com/blogs/inuitart/6751746-inuit-art-history.

"Inuit Religious Traditions ." Encyclopedia of Religion. . Encyclopedia.com. 29 Nov. 2022 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

“Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit.” Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit | Government of Nunavut, 18 Nov. 2022, https://www.gov.nu.ca/culture-and-heritage/information/inuit-qaujimajatuqangit.

Jones, J. Sydney. “Inuit.” Countries and Their Cultures, https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/Inuit.html.

Nausbummer, Claudia. “The Tension between Tradition and Change - Gender Roles in Inuit Communities and the 'Double Burden'.” STAND, 7 Aug. 2019, https://stand.ie/the-tension-between-tradition-and-change-gender-roles-in-inuit-communities-and-the-double-burden/.

Nearles, Edmund. Nuit Identity in the Canadian Arctic . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288081347_Inuit_identity_in_the_Canadian_Arctic.

Walley, Meghan. “Exploring Potential Archaeological Expressions of Nonbinary Gender in Pre-Contact Inuit Contexts.” Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2018, pp. 269–89. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26775769. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

“Weather & Climate.” Travel Nunavut, https://travelnunavut.ca/plan-and-book/visitor-information/weather-climate/.

Wood, Darryl. Violent Crime and Characteristics of Twelve Inuit Communities in the ... 1997,https://www.researchgate.net/publication/34285493_Violent_crime_and_characteristics_of_twelve_Inuit_communities_in_the_Baffin_Region_NWT.